LEISURE, INVENTED

On imitation, rehearsal, and the desert

For a long time, America didn’t have a language for leisure. Not just for time off, but shared ideas about how rest should look, feel, and be lived.

In the late 19th century, when wealth arrived faster than cultural confidence, Americans looked elsewhere for inspiration. Mansions borrowed from France. Civic buildings from Rome. Social rituals from anywhere but home.

Watching The Gilded Age recently, this borrowing feels obvious in hindsight — ornament standing in for tradition, aesthetics doing the work of meaning. It’s tempting to read that period as naive or derivative, but it was also a culture rehearsing a way of living it hadn’t yet learned how to articulate.

Palm Springs would later do something similar.

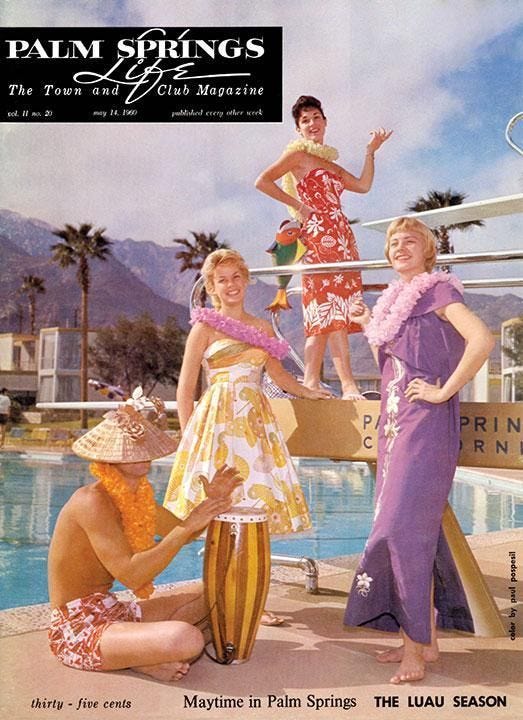

By the mid-20th century, postwar America found itself with time, mobility, air-conditioning, and disposable income. What it lacked was precedent — leisure had to be invented. Palm Springs, with its open desert landscape and proximity to Los Angeles, became a permissive stage for that invention. It largely existed to be elsewhere, removed from work, war, and routine.

Enter Polynesia.

Spend enough time in Palm Springs and its Polynesian-inspired houses can start to feel kitsch — aesthetic experiments taken a step too far. Their low-slung roofs, exaggerated eaves, tiki motifs, courtyards organized around pools feel out of place standing next to the more familiar midcentury lines we’re used to seeing now.

If the reference isn’t obvious from the architecture alone, the names make it explicit. There’s Royal Hawaiian Estates, by Donald Wexler and Richard Harrison, often cited as a prime example of “Tiki Modernism.” And scattered throughout Vista Las Palmas are Charles DuBois’s Swiss Miss houses, or Alohaus, a loose portmanteau that folds alpine geometry into a fantasy of island life.

It’s easy to read this as themed architecture, but that framing mistakes the order of operations. These houses weren’t chasing new aesthetics for their own sake. They were trying to solve a problem that hadn’t yet found its form: what does “rest” as a culture look like?

The Polynesia being invoked wasn’t a real place so much as a collective projection — ease without obligation, pleasure without consequence, distance from Western restraint. These houses offered a way to step out of American life without leaving it entirely. They were sincere, even if they were imprecise.

Authenticity, as it’s often used in architecture, tends to assume an origin story — a stable culture expressing itself truthfully. But when a society is still learning who it wants to be — when there is no inherited language of leisure — form becomes a proxy. Fantasy fills the gap until something sturdier takes hold.

Palm Springs made room for that awkward middle stage, and in many ways it could only have happened there. Before the desert was understood as a living landscape in its own right, it was treated as a blank canvas for experimentation. The stakes were lower here. Lawns were already artificial, pools already improbable, and shade itself was already constructed. Nothing pretended to be natural, so nothing had to apologize for being invented. In that environment, the desert became a stage for performance.

Seen this way, the Polynesian houses aren’t embarrassing outliers in an otherwise refined modernist narrative. They belong to the same transitional moment. Before a culture can design with confidence, it tries on other identities. Borrowing precedes authorship. Imitation is rehearsal.

I’ll admit, I’m often skeptical of newly invented aesthetics. Too often, they collapse into pastiche, and novelty is mistaken for progress. But that critique assumes aesthetics were the goal here, and they weren’t. The goal was emotional. These houses were testing how much fantasy was required to feel at ease.

Over time, that question found different answers. Palm Springs’ more restrained modernism — the crisp lines, the confidence of proportion, the quieter material palettes — didn’t emerge in opposition to fantasy so much as after it. Once leisure had been lived, it no longer needed to be exaggerated.

These Polynesian houses feel dated now, but they remind us that architecture often appears clumsy at moments of cultural transition. When ways of living change faster than the stories we tell about them, buildings step in to bridge the gap. Sometimes they do so elegantly. Sometimes awkwardly. But almost always earnestly.

Today, authenticity is treated as a moral category. Yet many of our most beloved spaces began as imitations — sincere attempts to live differently before we knew how to explain ourselves.

The question, then, isn’t whether these houses were authentic. It’s whether they worked.

Palm Springs suggests they did, at least for a time. Maybe that’s what dream spaces really are — not visions of a perfected future, but transitional architectures. Places where a culture practices becoming what it doesn’t yet know how to name.

MODERNISM WEEK — THE LINEAR FIELD GUIDE

Modernism Week transforms Palm Springs every February. For ten days, the desert becomes an architecture symposium — home tours, screenings, and special events.

Wow I loved this read. That idea of the desert being a blank canvas is something new for me but really makes sense in light of what I’ve seen in the past.

Brilliant piece on how cultures rehearse before they articulate. The idea that fantasy isnt frivolous but functional in those transitional spaces really reframes what we dismiss as kitsch. I was reminded of how certain design movements in the 60s struggled with this same legitimacy question, until evnetually the aesthetics felt earned rather than borrowed.